La Strada Poland is a member of GAATW in Warsaw, Poland. In May 2024, Vivian Cartagena from the GAATW secretariat conducted this interview with Joanna Garnier, member of La Strada, to learn more about the work of the organisation, the contexts in which it operates, and the communities it supports.

Vivian: Thank you, Joanna, for taking the time to talk with us! I would like to know more about La Strada Poland. How and why was it founded? We know that this organisation is a part of La Strada International, but what led to its founding in Poland?

J: It was a very long time ago. We started in Poland in 1995, and then 10 years after La Strada International was founded. This idea came from the Netherlands, from the Foundation Against Trafficking in Women, which was founded in 1987 to help Latin American and Asian/Southeast Asian women forced into prostitution there. After the collapse of the Communist system in Poland, we had the Carnival of Solidarity. We had the first free elections in 1988, with a totally new parliament and government; this was among the first signs of change in Europe.

We had lived in a closed country but after 1990, people started to leave Poland to work abroad because the borders were opened after 50 years. An organisation in the Netherlands, STV, noticed that more and more women from Central and Eastern Europe were forced into prostitution in Utrecht. So, they decided to establish cooperation with the Polish Feminist Association in 1992, and this was the beginning of cooperation between the two organisations. Then, in 1993, there was a lecture by Trjintje Kootstra from STV, a very well-known academic, who came to Poland and talked about forced prostitution and trafficking in women in the Netherlands.

This is our story, the start of cooperation between the Foundation Against Trafficking in Women from Utrecht (the Netherlands) and the Polish Feminist Association. They started working together around 1992/1993. At this time there was a Polish-Dutch seminar on the problem and finally the proposal to the European Union to start the first programme was submitted. It was called Programme Prevention of the Trafficking of Women in Central and Eastern Europe. We started this programme in 1995 and during this time the Polish Feminist Association decided to finish their work. So, there was money to start, there was money for projects, but there were no people to work with or employ.

The organisation was named La Strada during our first meeting in the Netherlands in October 1995 as a tribute to a very famous Italian movie, La Strada, in which the central character, Gelsomina, is a victim of human trafficking. She works in a circus and the movie is about her partnership with her very rude employer. This movie is significant for the anti-trafficking movement.

After one year of the prevention programme, the legal entity of La Strada Foundation Against Trafficking in Women was established and La Strada Poland started with La Strada Czech Republic and the Netherlands, where their headquarters is. Then, in 1997 Ukraine joined us, and Bulgaria in 1998.

Vivian: Interesting. Could you tell me more on how La Strada Poland found its way working as an anti-trafficking organisation?

J: Well, in these 30 years, we have done the same kind of work. Nevertheless, trafficking has changed. It really has. At the beginning, we worked only with victims of forced prostitution and only women. But in 2006, we changed the name to Foundation Against Trafficking in Persons and Slavery when others started to ask us for help. For example, foreign people and others started to be exploited in regular jobs, not only prostitution.

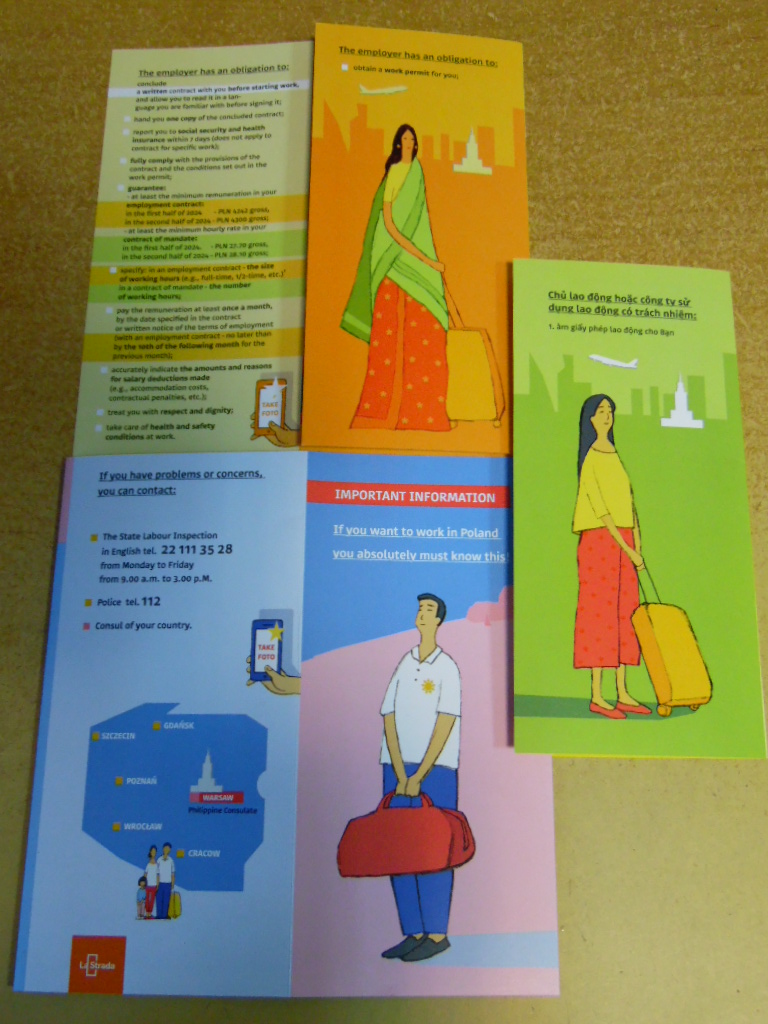

So, as La Strada Poland, we began working on three campaigns. The first campaign was “Media Lobbying’’ which was meant to talk to the media to create awareness about human trafficking in society. We were also lobbying for legal changes, asking for improvements in legal protection of victims of human trafficking. The second campaign was “Prevention and Education’’ for which I was the manager. It was aimed at educating school children about human trafficking, as well as creating materials and programmes. We were also teaching people about safe migration, working abroad, among other topics.

The third campaign was “Help and Support for Victims’’. In our early years, we had no money to support the victims. Sometimes we wonder how we managed to work without money. At that time, women were asking for help, and we did not have money or shelter.

After those three campaigns, we have continued to help the victims, talk to the media, and do lobbying which is really efficient. We still teach about human trafficking. We now train professionals, the police, border guards, prosecutors, judges, social workers, etc. We even run a shelter now for women here in Warsaw.

We have two additional accommodation opportunities for people. There are two flats where we can allocate people that need shelter. We provide professional support for them, much more than before. However, now anti-trafficking has changed, and it is sometimes very complicated to assist everyone.

Vivian: What do you mean by “human trafficking has changed’’? You mean the dynamics?

J: I would say that the first thing that has changed is the increased use of the internet to recruit people. When we started, people were reading job advertisements in newspapers, on the streets, or listening to other people's experiences. Now, more than 60% of the victims we assist have been recruited online.

The second change is that, currently, we have more cases of forced labour. Not only for forced prostitution, as before. Sex work has also changed, thanks to the internet. In my opinion, sex industry in Poland is not as cruel as it was years ago. Now, as we see it, women choose to be into sex work, they can choose to sell sex. Of course, we still have cases of forced prostitution or sexual exploitation, sometimes quite terrible cases.

The third change we see is that Poland has changed from an emigration country to an immigration country. In the early 2000s, we used to work with only Polish citizens who left the country to work somewhere else. But now foreigners are the majority. From around 300 people that we are assisting, we have only received 18 Polish people so far. Poland has become attractive for Asians, Africans, and now for Latin Americans. Polish people, on the other hand, still prefer to work in Germany, Norway and Sweden.

Vivian: I have a question related to this. As you mentioned, the Polish people have relied on labour markets in other European countries. Does La Strada Poland work with Polish women abroad who have been victims of human trafficking?

J: Yes, we also work with Polish people abroad because they still call us or get in touch with us. However, most people don’t want to come back to Poland. But if they do, we support them with advice. This week I received an email from a Polish person who was in Italy and wanted to come back. We offer such people a place in our shelter.

Currently, we are running a public programme financed by the government named the National Intervention and Consultation Center for Victims of Human Trafficking. This project is to help the victims directly.

Vivian: And in regard to these cases of women, whether within Poland or abroad, what are the main challenges and dynamics?

J: Well, we do a lot of advocacy work and lobbying. However, when we talk to decision-makers about these cases of women and girls forced into prostitution abroad, they may listen to you and say “oh, poor Polish girls and women’’, but when it comes to supporting women victims of trafficking in Poland, that is much easier.

Nowadays, the trafficker is the person running job agencies and financial enterprises that looks good, and even speaks English. Colleagues who are active on LinkedIn have come across owners of these agencies there!

This is also related to the cost of production in Poland. If you want to employ people, you have to pay health insurance, social security, and taxes in addition to the salary. Labour cost in Poland, specifically for employers, is almost 50% of the resources. If you want to employ the person legally, you have to spend much more than employing someone from Bangladesh. I think this is why the employment rate is falling in Poland.

Concerning foreign workers, the official employer is the agency, not the enterprise. They recruit people and employ them. The enterprise has only a settlement with the agency. They pay the agency, and they are the ones who are giving the jobs to foreigners, thus pay their salary. These are the agencies that are now recruiting people, for example, from Colombia. What is happening now is that people from Colombia and other Latin American countries can come to Poland and to the Schengen zone without visas for up to 90 days, as tourists. That’s when agencies take advantage of this and tell them to come to Poland to start working. Meanwhile, they “legalise’’ them by applying for residence and work permits. In most of the cases, they do receive the work permits, but that doesn’t mean they are totally legal.

Overall, the current situation is very difficult not only for us as an organisation but also for people who are victims of human trafficking. That’s why we have been very eagerly doing advocacy work targeting decision-makers to help victims have quicker paths to apply for residence permits. Five years ago, we tried to do this for twenty victims, but now, we are looking after 200 of them. If the bureaucratic processes were faster, we wouldn't have so many of them waiting for the residence permit.

Vivian: So, in summary, would you say there is a significant lack of social protection for victims of human trafficking?

J: Yes. However, we now think that the timely issue of the residence card and access to health insurance will probably solve many of the problems that we are currently facing.

Vivian: Joanna, thank you for this conversation; I don’t have any more questions. Is there anything you’d like to add?

J: Yes, I would like to highlight that even though we consider La Strada Poland as an organisation that is doing a very good job, when it comes to asking for support, we face barriers due to the fact that human trafficking is not a priority for the government. Victims of human trafficking are not seen as persons deserving of help or empathy. On the contrary, they are seen as naive people who can easily be cheated and who deserve to be in this situation. Victims of human trafficking are held responsible for what has happened to them.

This is a common perception worldwide, not only in Poland, and this has to change!

Vivian: Yes, unfortunately, it is a common way of thinking in other countries, too. Thank you, Joanna, for such a deep conversation. It was a pleasure learning more about the work of La Strada Poland.